Hard red wheat is the workhorse of the flour world. This is the main type of wheat in general commercial all-purpose flour. 95% of the wheat grown in Kansas is hard red (winter) wheat. In contrast, the wheat region of Washington (my homeland) grows more soft white wheat.

For this batch of pasta, I was using spring hard red (grown in the northern plains with a shorter growing season), which has a higher protein content than its winter sibling. It may have been a little bit of a hearty overkill, but my idea was to make a rustic high extraction (near whole wheat-type) pasta.

I had actually milled and bolted the flour a week earlier, leaving it as straight flour (bran and germ removed) in the fridge until I had time to put it to use. The extraction rate for this straight flour was disappointing though, coming out a little low at 60% of the whole berry using the #40 mesh sieve. 70-75% would be the ideal range, although I don’t generally get that high. I think that is more the result from high efficiency roller mills. I will have to see what happens with the next batches, but I am worried that my mill needs some maintenance.

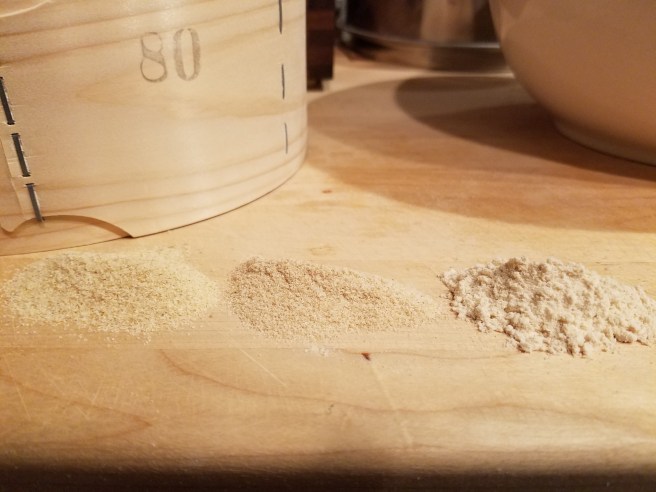

Originally, this pasta was going to be made with 100% straight flour, but once I started working with it I felt it was too rough. Instead the final flour make-up was 200g of the straight flour and 100g of fine flour. The fine flour was just the same straight flour passed through my #80 mesh sieve. I find the #80 mesh to be the lowest grade that produces a soft flour approaching general all-purpose texture and properties.

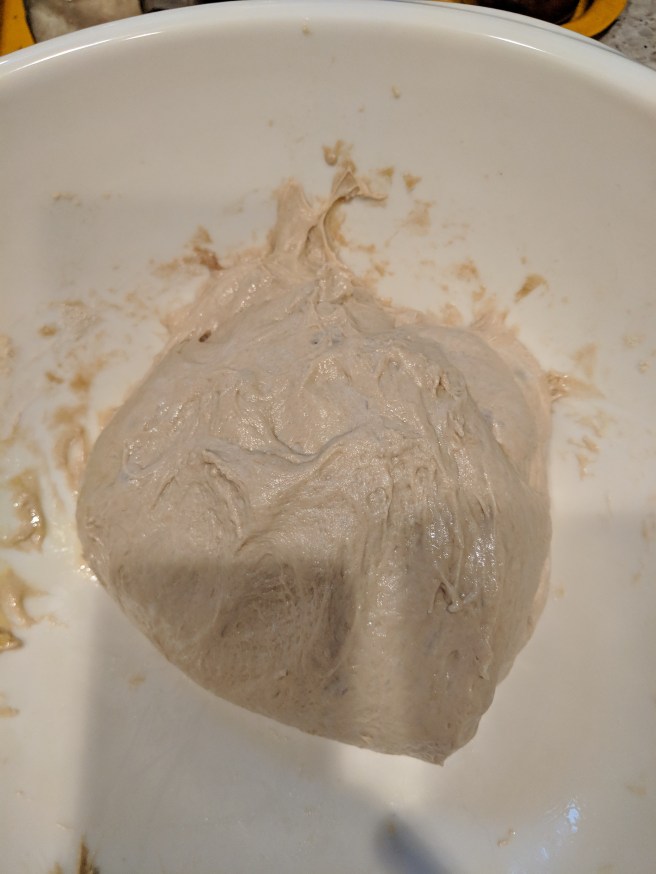

For the dough, I added a sprinkling of sea salt to the flour and added three whole eggs to the center flour well. I should have used four eggs (or probably just an extra yolk), as this flour was a little dry and fresh milled flour usually needs more liquid. Instead though, I ended up with a good amount of flour that didn’t get incorporated into the dough. I wasn’t worried though as I didn’t need that many ravioli for just a small family dinner.

The dough was a little on the tough side (strong spring wheat gluten), but still rolled out smooth and even with an overall nice feel. A stuffed pasta dough does need to be tougher than a dough for noodles. After resting the dough, I hand rolled and cut it into 3 inches strips.

The ravioli filling was roasted root vegetables (potatoes, carrots, celery root, and turnip), well smashed up and mixed into ricotta, Parmesan Reggiano, parsley, olive oil, lemon juice, and fresh sage.

They didn’t come out beautiful, but they are the best ravioli that I have made before, as far as being a consistent size and well formed.

The final dish was pretty tasty, in my opinion. The pasta was a bit “wheaty.” My daughter didn’t seem to be a huge fan, but she ate maybe one ravioli after I pulled one from the bottom of the dish that didn’t have any chopped parsley on it (a small victory). I was worried that the rustic pasta would be too hearty for the subtle flavors of the root vegetables, but it carried the flavors well.

The finished dish was made by rendering down a little pancetta, frying some sage leaves in the fat, then giving the ravioli a toss in some of fat and butter, and lastly adding in the remainder of the roasted root vegetables and tossing the pancetta and sage leaves back in the pan. Drizzled with a finishing olive oil, grated Parmesan Reggiano and chopped parsley to top it off.

Fine fresh-milled flour has a rich white color and a soft vegatal flavor. It doesn’t taste like much compared to a fresh ripe tomato, but it tastes like actual food compare to commercial flour.

Fine fresh-milled flour has a rich white color and a soft vegatal flavor. It doesn’t taste like much compared to a fresh ripe tomato, but it tastes like actual food compare to commercial flour.

After resting the dough for an hour or so, I cut it in quarters and rolled out pasta dough snakes. This is probably the most fun you can have making pasta.

After resting the dough for an hour or so, I cut it in quarters and rolled out pasta dough snakes. This is probably the most fun you can have making pasta.

Rolling with the KitchenAid attachment is so much easier than my old counter-(poorly)mounted hand-cranked roller, which I tossed unceremoniously in a fit of meh one day. This is definitely going to help my long flat noodles and stuffed pasta skills. I love to hand roll pasta and won’t give that up, but this is a nice tool to have.

Rolling with the KitchenAid attachment is so much easier than my old counter-(poorly)mounted hand-cranked roller, which I tossed unceremoniously in a fit of meh one day. This is definitely going to help my long flat noodles and stuffed pasta skills. I love to hand roll pasta and won’t give that up, but this is a nice tool to have.