Spelt is apparently the source of some controversy. That is, is spelt a subspecies or wheat or a close cousin of wheat. The FDA says it is a wheat and the current genetic-based taxonomy appears to classify it as such. Other than for sciencey types, I would guess the debate is driven by a desire to avoid the bad reputation of wheat in certain nutritionally-minded circles. I don’t think wheat is a bad thing, so it doesn’t bother me one bit to think of spelt as a wheat.

I will admit that I used to scoff at spelt. It seemed that the first generation of anti-wheat fever resulted in everything being made of spelt–spelt tortillas, spelt bread, spelt pasta, spelt everything. (I am happy that times have progressed and now we are starting to see emmer or other heritage wheat varieties getting top billing.) With the exception of spelt pasta, which is and will always be a travesty, I have come around. So I decided to make some spelt pizza.

My spelt berries are branded as Vita Spelt (who are decidedly on the spelt-not-wheat side of the “controversy”). These berries have a heavy bran, which I sifted off to leave a 75% extracted/bolted spelt flour. I have been adding soft white flour to achieve a lighter flour and decided to go to a higher 47% soft white ratio (ultimately a mistake, it should have been a much lower ratio).

Stone ground soft white on the left, spelt on the right (post-extraction). I really need to tile my backsplash–this is getting ridiculous.

Dough ratios. My goal was 500g of dough to make two 250g pizza crusts, using a high, 70% hydration.

Dough ratios. My goal was 500g of dough to make two 250g pizza crusts, using a high, 70% hydration.

- Spelt flour–154g (75% extraction)

- Soft white — 137g (80% extraction)

- Water — 200g for 70% hydration

- Salt –5g

- Yeast — 2g

After mixing, the dough was ready for some rising and folding. This dough ultimately was left overnight in the fridge. The following day, the dough was left to rise at room temperature, split in two, shaped, wrapped and placed back in the fridge for a couple hours before dinner time. I loosely followed some guidance from Ken Forkish’s Flour Water Salt Yeast on the principles of good pizza dough.

mixed dough reading for folding

fold 1

still folding

adding tension

When it came time to actually shape the actual pizza round, it was very apparent that the spelt (even further weakened by too much soft white flour) was not going to hold up well to stretching. I did a couple hand stretches of the dough, but in the end I had to just knuckle it into shape. See here in the cast iron skillet.

So, how was the final product. One with zucchini and onion, the other with uncured salami and pickled garlic (one of my new favorite pickles). Sauce was very simple, sauteed garlic in olive oil and a can of pureed tomato, with red peppers flakes and oregano. Overall, the pizza was fine, really nothing special, but a worthwhile experiment to test the boundaries of spelt. The dough was chewy and flavorful and not too whole-wheaty, but lacking nice crusty airpockets. My wife even ate most of her crust. A huge victory.

Conclusion, spelt can make perfectly acceptable homemade pizza dough if you accept its limitations.

The reality is that without a pizza oven (or even a pizza stone in my case), you simply cannot make great pizza at home. Sometimes though, a less than perfect homemade pizza is what the day calls for.

The reality is that without a pizza oven (or even a pizza stone in my case), you simply cannot make great pizza at home. Sometimes though, a less than perfect homemade pizza is what the day calls for.

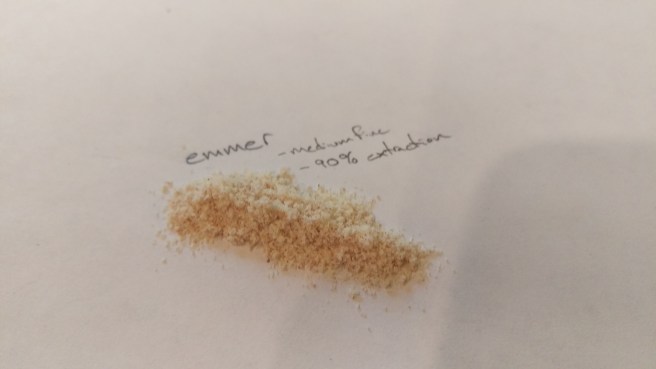

Despite my appreciation for whole grain (or high extraction almost whole grain), sometimes you really just want some fine white flour. I previously purchased a #50 sifter that I thought would get me close, but it was still only getting me to around a ~75% extraction. The resulting flour was producing more of a whole wheat than white bread. After some research, I realized that I needed to step-up my sifting game. So here it is, an Advantech #120 stainless steel scientific grade sieve. This gets flour particles down to 125 microns (which I will refer to as super fine).

Despite my appreciation for whole grain (or high extraction almost whole grain), sometimes you really just want some fine white flour. I previously purchased a #50 sifter that I thought would get me close, but it was still only getting me to around a ~75% extraction. The resulting flour was producing more of a whole wheat than white bread. After some research, I realized that I needed to step-up my sifting game. So here it is, an Advantech #120 stainless steel scientific grade sieve. This gets flour particles down to 125 microns (which I will refer to as super fine).

my wife is constantly running out of memory on her phone due to an insane number of baby photos and videos being texted on any given day. I was just about to explain that the sifter is #50 mesh and does a great job of producing a fine flour with more extracted bran than my previous sifter.

my wife is constantly running out of memory on her phone due to an insane number of baby photos and videos being texted on any given day. I was just about to explain that the sifter is #50 mesh and does a great job of producing a fine flour with more extracted bran than my previous sifter.

Dough ratios. My goal was 500g of dough to make two 250g pizza crusts, using a high, 70% hydration.

Dough ratios. My goal was 500g of dough to make two 250g pizza crusts, using a high, 70% hydration.

The reality is that without a pizza oven (or even a pizza stone in my case), you simply cannot make great pizza at home. Sometimes though, a less than perfect homemade pizza is what the day calls for.

The reality is that without a pizza oven (or even a pizza stone in my case), you simply cannot make great pizza at home. Sometimes though, a less than perfect homemade pizza is what the day calls for.